While there has been a noticeable increase in Teslas on the road, a new entrant to the Australian market, BYD, has been making massive strides in its deployment of electric vehicles globally, particularly through the use of its revolutionary Blade Battery.

From H2 2021 to H2 2022, Adamas Intelligence reported a 64% increase in deployed battery capacity from 177.5 GWh to 291.7 GWh. Tesla and BYD were together responsible for more than 30% of all battery capacity deployed on the roads in 2022 H2, nearly as much as their next 15 competitors combined.

In terms of demand, this has important implications for battery mineral producers and investors in the sector.

Independent advisory service, Adamas Intelligence has just released its 8th biannual Research Report H2 2022, reviewing the performance of the EV industry and ramifications for the battery metal supply chain.

The report sets out some interesting statistics on EV metals demand.

We think there are more pertinent considerations for the mineral producer to note, which we will outline below. But first to the Adamas report.

Global passenger EV registrations lifted 38% over the previous H2 2021 period. Leading the demand charge was Asia Pacific, with a 53% increase in passenger EV sales year-on-year, lifting Lithium demand 74%, Nickel 44% and Cobalt 45% into the region.

This is important

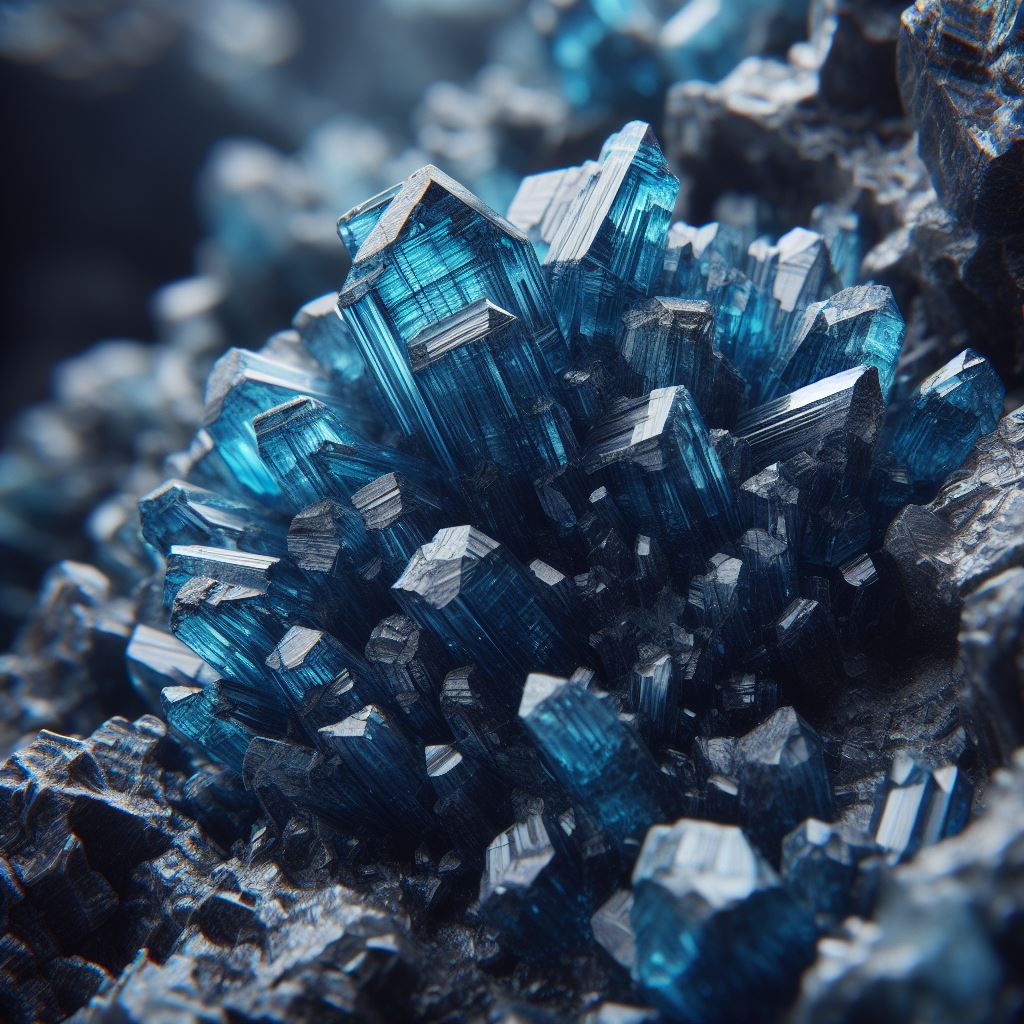

In H2 2022, Lithium Iron Phosphate cells in watt-hours lifted 129% over the previous corresponding period thanks mainly to the popularity of BYD cars and the company’s revolutionary Blade Battery.

With long life, reduced fire risk, and a chemistry make up of lithium, iron and phosphate, eliminating nickel, cobalt and manganese, this is something close rival Tesla is increasingly aware of.

BYD’s Blade Battery still uses lithium, and in H2 2022, passenger EVs used 174,000t of lithium carbonate, up 62% on H2 2021.

Despite the Blade Battery’s popularity, passenger EV nickel demand lifted 44% over H2 2021, cobalt demand lifted 37% and manganese demand was up 39%.

Despite the positive demand for these commodities, battery mineral producers should be aware that there is a shark in the water, and that shark goes by the name of BYD. If its sales growth continues at this pace, there is every chance that other producers will shift their battery chemistry across.

Somewhat more immune to attack is graphite with demand lifting 68% over the previous corresponding period. Nevertheless, as General MacArthur said, “There is no security on this Earth, only opportunity,” very true for the battery industry, as chemistries continue to evolve at a rapid pace.

EVs are not a religion, at least not yet

In the short term, we think that EVs will remain a niche product for the very well off and ironically for the relatively less well-off people in places like India and China where micro EV cars and motorcycles using lithium batteries are selling in large numbers.

The full sized Australian car/SUV is a different story, much more situation specific, and requiring deep pockets.

Why?

EV prices are not following a normal cost curve where increased production volume results in reductions in price. We would suggest that unlike digital products, EVs are running up against the rules of physics and chemistry. This is also failing to create the normal technology exponential product uptake as seen with computers or digital cameras for example.

These market dynamics are starting to become apparent to both the lithium market and regulators, where the EU, after questioning by Germany and Italy, recently delayed a planned vote to end sales of new CO2 emitting vehicles in 2035.

It is not all bad news for commodity producers, we see battery powered tools and other applications as likely to become increasingly market dominant, something the investment market may be overlooking, if it is not lost on the building market, where tradies still using electric cords are increasingly a thing of the past.

EVs are here to stay, but Western adoption may be somewhat slower than anticipated due to a range of factors, one of which is likely to be on the supply side with an inability to secure sufficient source material to keep up with demand.

Andrew Quin is a former Macroeconomic Strategist for Australia’s largest full service stockbroker, HNW fund manager, and published Author. He holds a Masters in Mineral Economics.